CPI Asia Column edited by Vanessa Yanhua Zhang (Global Economics Group) presents:

Developments in Criminal Enforcement of Competition Law in Korea by Hee-Eun Kim* (Covington & Burling LLP Brussels Office)

* Attorney at Covington & Burling LLP Brussels Office. The views expressed in this article are the author’s, and should not be construed as reflecting those of the firm or its clients. Thanks are due to Lars Kjølbye and Nancy B. Rohn for their comments.

Korea’s New Presidency and Competition Law Enforcement

On December 19, 2012, Korea elected Ms. Park Geun-hye to lead a new government for the next five years. Not only is Ms. Park the first woman president of Korea, she is also the daughter of former president Park Chung-hee. Mr. Park is regarded as the driving force of the remarkable economic growth through the 1960s and ‘70s, the period which began the per capita increase in Korea’s nominal GDP from US $100 in 1962 to more than US $22,000 in 2012.

While the “pie” has grown enormously in only half a century, economic and social issues from the rushed industrialization and unequal distribution of wealth pose challenges to Korea’s future growth. Hence, a balance between “economic democratization” and continued expansion tops President-elect Park’s agenda of economic and industrial policies. As part of these policies, she has pledged to facilitate fair and transparent competition among large- and small-sized enterprises and to protect underdogs in the market. Notably, she has proposed reform of the enforcement framework for the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act (“the MRFTA”) and related laws, including:

- amending provisions in the MRFTA which currently provide that only the Korea Fair Trade Commissions (“the KFTC”), a government agency responsible for public enforcement of competition law, can refer criminal offenses of the MRFTA to the Prosecutor’s Office, Korea’s public prosecutors;

- introducing “collective redress” and expanding the availability of “punitive damages” to encourage private enforcement; and

- adopting a number of provisions related to corporate governance of business conglomerates.

It is still early to predict how the proposals will ultimately be implemented, but the new presidency appears poised to improve the landscape of Korea’s competition law enforcement. While each of the above three topics is important, this short piece focuses on the first, namely a possible change to the criminal enforcement framework which currently grants the KFTC exclusive power to submit criminal offenders of the MRFTA to the Prosecutor’s Office. The background, institutional issues, and more substantive components of criminal enforcement and deterrence are briefly explored.

Overview of Competition Law Enforcement in Korea

The KFTC commonly employ administrative sanctions for enforcing competition law. Corporate offenders may be subject to a “surcharge” of up to 10 percent of the “relevant” sales, and to corrective measures such as cease-and-desist orders. Competition law offenders are also liable for private damage compensation, except when they prove the absence of intent or negligence on their part (Article 56 of the MRFTA). Victims of a competition law offense do not have to await the outcome of pending KFTC proceedings in order to bring a private damage lawsuit. Still, private enforcement is rarely used in Korea. In order to facilitate such enforcement, the KFTC is considering ways to support consumer groups bringing private damage actions.

Criminal sanctions can be imposed on corporate offenders (including directors and employees) as well as individuals. Notably, Article 66 of the MRFTA provides for a jail term of a maximum of three years and/or a criminal fine of up to KRW 200 million (approximately 140,000 Euros) for offenses concerning abuse of market dominance, merger control, cartel, and certain restrictions on business conglomerates. Article 67 of the MRFTA provides for a jail term of a maximum of two years and/or a criminal fine of up to KRW 150 million (approximately 106,000 Euros) for less serious offenses, such as unfair trade practices, resale price maintenance, and anticompetitive cross-border agreements. Articles 68 through 70 of the MRFTA set forth further details on criminal sanctions.1 Prosecuted cases so far have been concluded with criminal fines, without imprisonment yet.

The KFTC’s Exclusive Power to Make a Referral to the Prosecutor’s Office

While the KFTC imposes administrative measures, criminal sanctions are up to the Prosecutor’s Office. However, the Prosecutor’s Office cannot initiate such sanctions on its own. According to Article 71(1) of the MRFTA, it can do so “only after a complaint is filed by the [KFTC].”

The competition authority’s exclusive power to refer to criminal prosecution was included in the MRFTA enacted in 1980, on the rationale that a competition law violation has “distinguishable characteristics” compared to other criminal violations.2 In other words, violation of competition law is an economic crime that requires a robust analysis of legal and economic impact and the KFTC is deemed best suited to undertake such task.3 In 1995, the Constitutional Court of Korea considered whether this exclusive referral power infringed the right to equality and the right of access to courts. The Court upheld the KFTC’s exclusive role but also observed the need for balance:

“For effective enforcement and deterrence of anticompetitive conduct, administrative sanctions such as a corrective measure or a surcharge alone are not sufficient, and it is necessary to make use of criminal sanctions which have strong effect of psychological coercion. […] However, there is a concern that reckless criminal enforcement may chill business activity, and such a consequence achieves neither ‘promoting fair and free competition’ nor ‘encouraging business activity.’ Therefore, if possible, criminal sanctions against anticompetitive conduct should be limited to a case where the offense is so obvious that its impact on our economy and consumers is significant […]. The purpose of granting the KFTC exclusive authority to file a criminal referral is to achieve the goal of the MRFTA by allowing the KFTC to independently examine anticompetitive conduct through detailed market analysis […] and, depending on the market conditions of the relevant period, to regulate anticompetitive behavior only by administrative measures.”4 (unofficial translation)

Reflecting the Court’s ruling, the following checks and balances were subsequently introduced:

- The KFTC’s exclusive power is limited by Article 71(2) of the MRFTA which provides that “[i]f necessary, the [KFTC] shall file complaints together with the Prosecutor General for cases involving the offenses listed in Articles 66 and 67 [of the MRFTA] because the violation is deemed gross and considerable it may substantially suppress competition.” In this regard, the KFTC adopted a set of guidelines on the types and criteria of cases subject to a mandatory referral to the Prosecutor General;5 and

- The Prosecutor General can notify the KFTC of the existence of a potential criminal offense and request the KFTC to make a referral in such circumstances (Article 71(3) of the MRFTA).

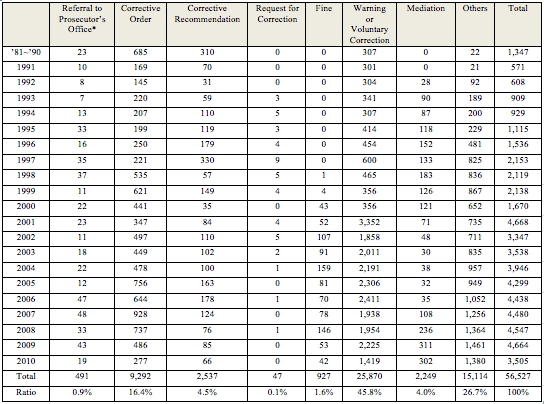

As shown in Table 1, the KFTC made referrals to the Prosecutor’s Office in 491 out of the total 56,527 cases the KFTC handled from 1981 to 2010.6 Some criticized the low percentage (0.9%) of referrals to the Prosecutor’s Office, although it should be noted that the KFTC is obliged to process all cases filed with it. The total number of cases (56,527) includes many involving relatively minor offenses which would not normally be referred to the Prosecutor’s Office. If the scope were limited to illegal cartel cases from 1981 to 2010, the ratio would rise to 44 out of 504 (11%).7

Table 1. Number of KFTC Cases by Measures

Source: KFTC Statistical Yearbook of 2010, page 32

*Note: The number of the referrals to the Prosecutor’s Office includes not only the referrals made under the MRFTA but also those under other related laws concerning unfair labelling and advertising, subcontract, etc. For example, only 4 out of the total 19 referrals in 2010 were brought pursuant to the MRFTA.

Challenges to the KFTC’s Exclusive Referral Power

Despite the introduced improvements in institutional checks and balances, the KFTC still faces criticism that its exclusive referral power should be further limited. In the wake of several recent domestic cartel cases, critics argue that criminal enforcement must be pursued vigorously to increase the level of deterrence. Pointing to the ‘low’ percentage of referrals, they claim that one way to strengthen such enforcement is to limit the KFTC’s exclusive referral power so that more criminal cases can be pursued through other routes. Without the KFTC’s exclusive referral power, victims of a competition law offense could file a complaint directly with the Prosecutor’s Office or the latter could itself launch an investigation and prosecute offenders.8

The KFTC raises a number of counterarguments: first, the percentage of criminal referrals (as noted, 11%) is in fact relatively high in comparison with other OECD member countries; second, as the Constitutional Court noted, the KFTC is best placed to perform economic analysis of harm and to assess whether anticompetitive conduct is “gross and considerable”9 so that criminal sanctions must be sought; and third, as most cartel activities are revealed through leniency applications, it is important to maintain incentives to apply for leniency. (Currently, the KFTC does not make a criminal referral against successful leniency applicants.) If the Prosecutor’s Office were to start pursuing criminal charges against leniency applicants, it could become challenging to manage the leniency program.10

The Relationship between the KFTC and the Prosecutor’s Office: Lessons from the UK?

Limiting the KFTC’s referral power is likely to increase the influence of the Prosecutor’s Office over competition law enforcement. In terms of institutional design, the relationship between the UK Office of Fair Trading (“the OFT”) and the Serious Fraud Office (“the SFO”) – the UK’s public prosecutors for serious or complex fraud except in Scotland – may provide useful guidance. After criminal sanctions against criminal cartel activity were introduced in 2002,11 the OFT and the SFO agreed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) setting out the basis for their cooperation. In relation to criminal referrals, this MOU provides that:12

- If the OFT receives information that criminal cartel activity may have occurred, the OFT will undertake any necessary initial criminal enquiries. If the SFO receives information suggestive of criminal cartel activity “prior to any related referral from the OFT,” the SFO will first forward such information to the OFT so that the OFT can perform any necessary initial criminal enquiries (Paragraph 3);

- If, upon the initial check (and informal discussions with the SFO), the OFT identifies a criminal cartel case possibly falling within the SFO’s ambit, the case will be referred to the Director of the SFO (Paragraph 4);

- If the SFO accepts the OFT’s referral, a criminal case team will be formed consisting of both SFO and OFT officials under the leadership and direction of an SFO case controller (Paragraph 6);

- The SFO makes a decision to cease SFO-led cartel investigations or to prosecute offenders in consultation with the OFT (Paragraph 14).

The MOU provides further arrangements between the SFO and the OFT on case team composition, decision-making during investigations, dispute resolution within the case team, and leniency.

It is noteworthy that the OFT appears to play an essential role in performing initial enquiries to determine whether criminal cartel activity requires the SFO’s involvement. Also, somewhat similar to the way in which the KFTC’s exclusive referral power functions, private prosecutions can be submitted only with the OFT’s consent.13

A Few Thoughts beyond Institutional Design

Kovacic and Hyman observe that, while multiple enforcement bodies serve “distinct purposes,” multiplicity also has its “costs.” They note that the risks associated with an institutional change can be reduced if a “process of patient experimentation, reflection, and benchmarking” is followed.14 In the context of the announced reform of Korea’s competition law, such a process could productively look beyond the institutional aspects to also examine the substantive components of criminal enforcement, including review of the penal provisions under Korean competition law (notably, Articles 66 and 67 of the MRFTA).

Such broader examination could cover a range of related issues. While criminal sanctions in many jurisdictions primarily target hardcore cartel offenses such as bid-rigging, the penal provisions in the MRFTA apply to almost any type of anticompetitive conduct, including minor violations. Has the broad scope of these provisions contributed to deterrence? Furthermore, the limited level of criminal sanctions actually imposed may well have undermined such deterrence. While the law provides for a maximum three-year jail term and/or a criminal fine of up to KRW 200 million (approximately 140,000 Euros), the criminal fines charged to individuals so far have not exceeded KRW 10 million (approximately 7,100 Euros), apart from the absence of imprisonment so far. Finally, it would probably make sense to balance any changes to the current criminal enforcement system with the benefits of the leniency program.

(Click here for a PDF version of the article.)

1 An English translation of the MRFTA is available at http://eng.ftc.go.kr.

2 Id. (discussing that it can also “enhance effectiveness of the leniency program by inducing suspects to cooperate in KFTC investigations”).

3 For similar reasons, Korea’s National Tax Services (NTS) has exclusive authority to refer certain tax law violations to the Prosecutor’s Office.

4 Cho v. KFTC, Constitutional Court of Korea Case No. 94 HeonMa 136 (July 21, 1995), page 8.

5 KFTC, KFTC Guidelines on the Referral of Violations under the Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act, KFTC Guidelines No. 140 (as amended as of August 20, 2012). A Korean version of the Guidelines is available at http://ftc.go.kr.

6 KFTC, Statistical Yearbook of 2010, page 32, available at http://eng.ftc.go.kr.

7 Jaeho Moon, KFTC, Cartel Enforcement Regime in Korea, GCR Law Leaders Asia-Pacific 2012 (March 2, 2012), available at http://eng.ftc.go.kr.

8 A 2007 attempt by the Prosecutor’s Office to prosecute competition law offenders without the KFTC’s referral was challenged in court.

9 Article 71(2) of the MRFTA.

10 E.g., The Aju Business, Interviews with Mr. Joong Weon Jeong (KFTC) on July 10, 2012 available at http://eng.ajnews.co.kr/view.jsp?newsId=20120710000011 and on July 29, 2012 available at http://japan.ajnews.co.kr/view.jsp?newsId=20120710000010, both in Korean.

11 Section 188 of the UK Enterprise Act 2002 imposes a maximum of five years’ imprisonment and/or unlimited fine for individuals who “dishonestly” engage in prohibited cartel activities such as price-fixing, limiting supply or production, market-sharing, or bid-rigging.

12 Memorandum of Understanding between the Office of Fair Trading and the Director of the Serious Fraud Office (October 2003), OFT 547, available at http://www.oft.gov.uk/shared_oft/business_leaflets/enterprise_act/oft547.pdf. In this respect, the OFT also has published several guidelines: e.g., OFT, Powers for Investigating Criminal Cartels: Guidance (January 2004); and OFT, The Cartel Offence: Guidance on the Issue of No-Action Letters for Individuals (April 2003), both available at http://www.oft.gov.uk.

13 Section 190 of the UK Enterprise Act 2002.

14 William E. Kovacic and David A. Hyman, Competition Agency Design: What’s on the Menu?, GWU Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2012-135; GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 2012-135, (November 21, 2012), available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2179279.

Featured News

EU Regulators Set to Clear Microsoft’s $13B OpenAI Investment

Apr 17, 2024 by

CPI

Biden Pledges to Block US Steel Acquisition by Japanese Firm

Apr 17, 2024 by

CPI

Canada Targets Tech Titans with New Digital Tax in 2024

Apr 17, 2024 by

CPI

EU Privacy Watchdog Calls for Meta to Offer Ad-Free Option

Apr 17, 2024 by

CPI

Japan’s Antitrust Overhaul Targets Tech Titans Like Apple

Apr 17, 2024 by

CPI

Antitrust Mix by CPI

Antitrust Chronicle® – China Edition – Year of the Dragon

Apr 16, 2024 by

CPI

Review Logic and Rules for Concentrations of Undertakings that Do Not Meet the Standard of Notification

Apr 16, 2024 by

CPI

China’s Review of Semiconductor Transactions

Apr 16, 2024 by

CPI

Key Challenges and Tips for Merger Control Filing in China for Listed Companies

Apr 16, 2024 by

CPI

Key Point Review: China SPC Antitrust Judgments in 2023

Apr 16, 2024 by

CPI