Rising tide of ‘Fix-it-first’ and ‘Up-front Buyer’ remedies in EU and UK merger cases

October 2016

CPI Europe Column edited by Anna Tzanaki (Competition Policy International) & Juan Delgado (Global Economics Group) presents:

Rising tide of ‘Fix-it-first’ and ‘Up-front Buyer’ remedies in EU and UK merger cases

by Dominic Long (Senior Associate, Allen & Overy LLP), Catherine Wylie (Associate, Allen & Overy LLP) & David Weaver (Associate, Allen & Overy LLP)

Issue in focus

‘Fix-it-first’ (FiF) and ‘up-front-buyer’ (UFB) remedies have long been a commonplace aspect of U.S. merger control enforcement, featuring in a significant majority of structural remedies negotiated by the Federal Trade Commission and Department of Justice over recent years.[1]

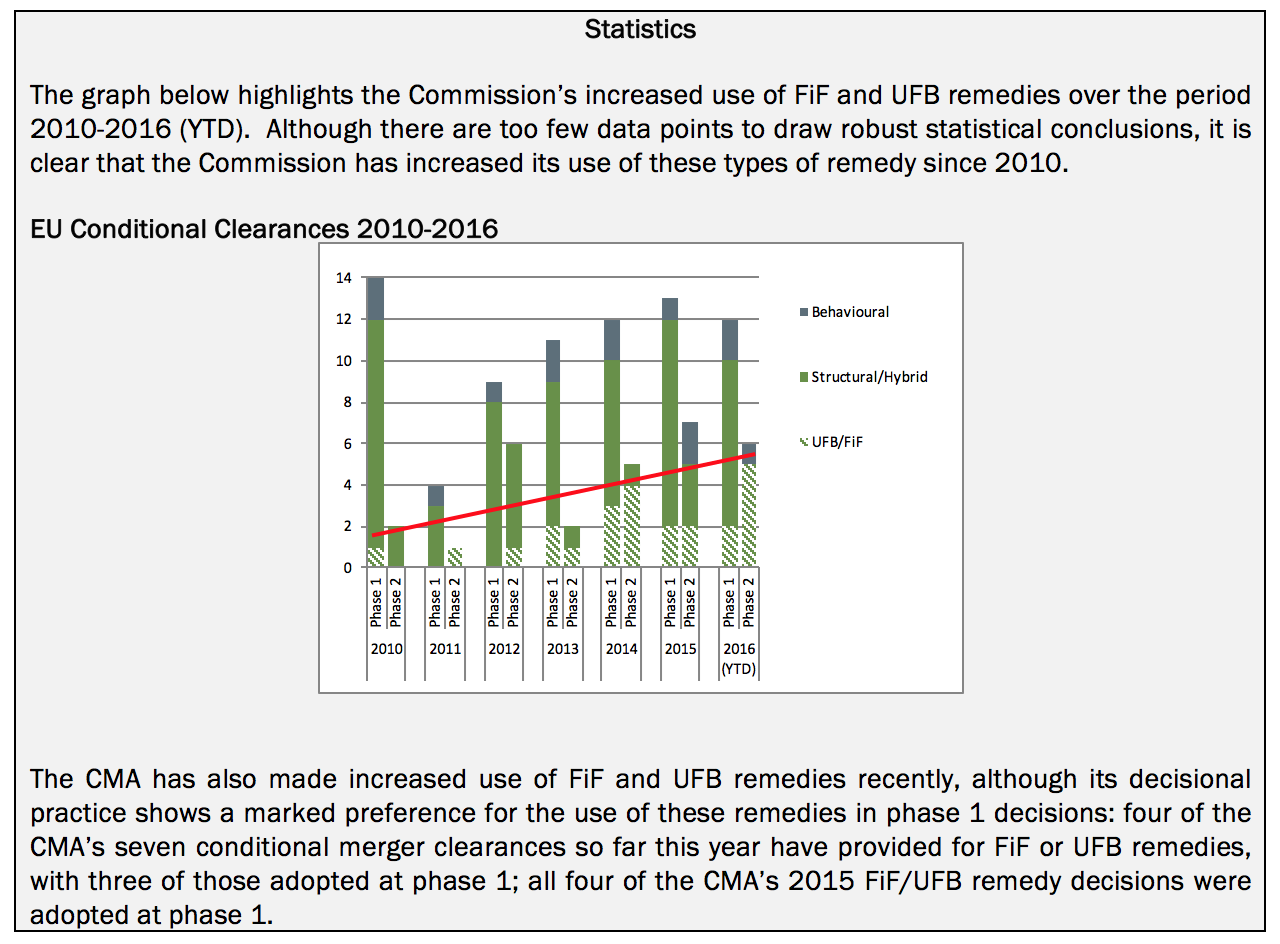

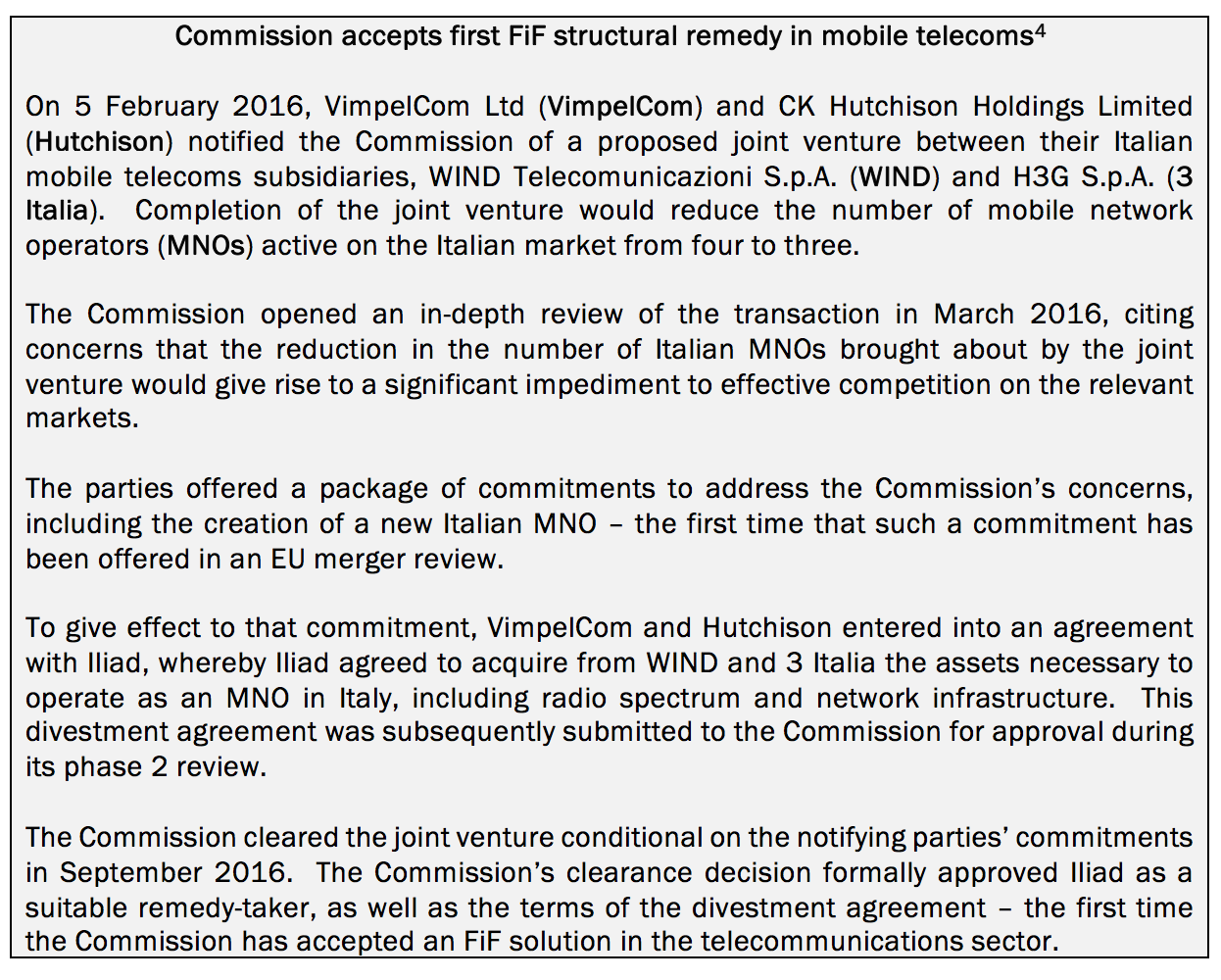

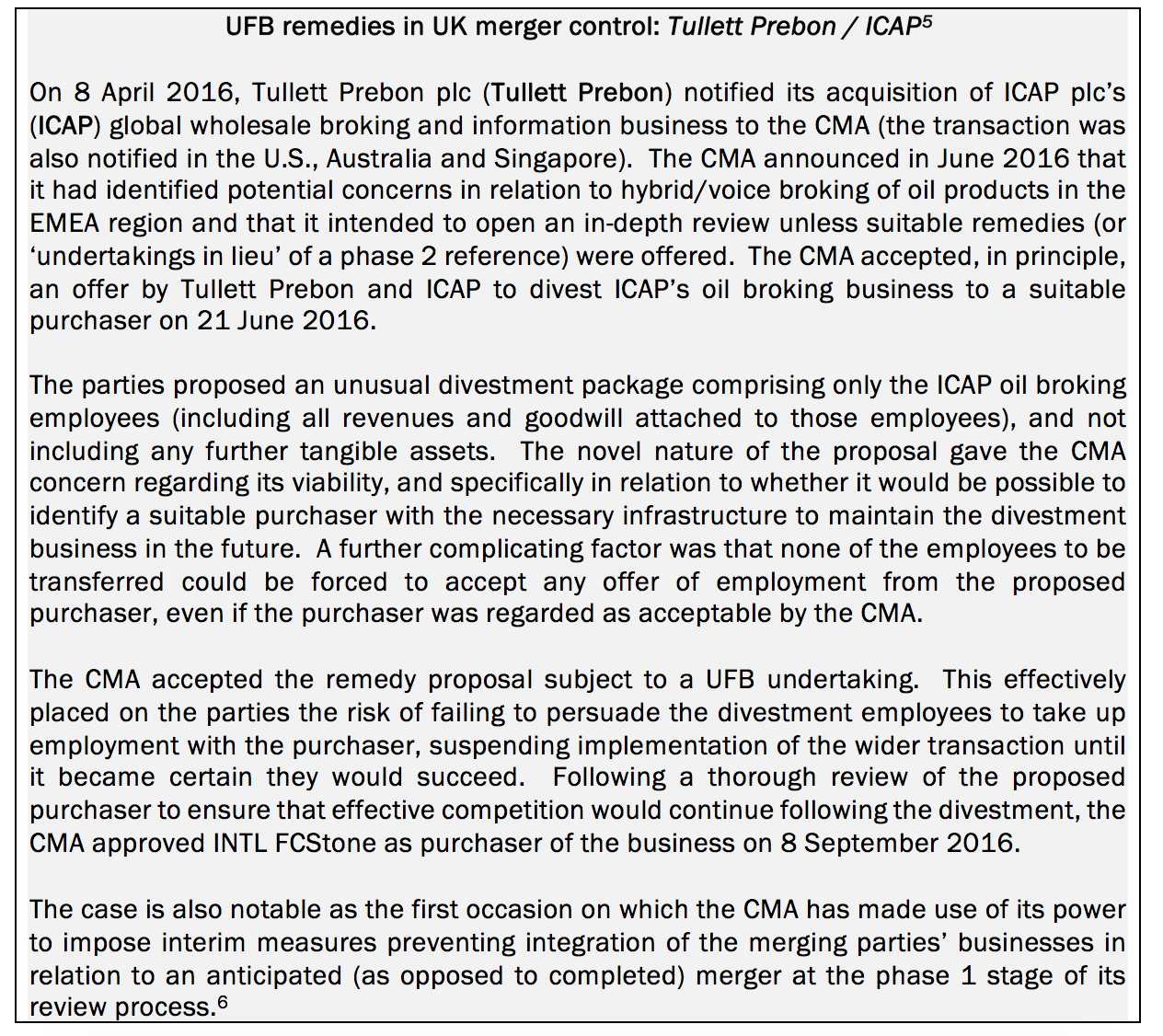

A convergence with this approach is now emerging from recent decision-making by the European Commission (Commission) and the UK Competition and Markets Authority (CMA). Since her appointment as European Commissioner for Competition on 1 November 2014, Margrethe Vestager has overseen 12 merger cases in which competition concerns have been resolved through the use of FiF or UFB remedies. By contrast, between one and three such remedies were agreed annually over the period 2010–2013. The CMA has also made increasing use of FiF and UFB remedies in recent merger control reviews, albeit with a preference for the deployment of such remedies at an earlier stage in its review process. Examples include the WIND / Hutchinson 3G joint venture (reviewed by the Commission) and Tullett Prebon / ICAP (reviwed by the CMA), both discussed below.

In this short paper, we first consider how these alternative remedy structures – the boundaries of which sometimes overlap – should best be understood, and the implications of each for merging parties. We also briefly consider how a break-up bid transaction structure may, in certain circumstances, effectively serve as an alternative to an FiF remedy.

What is a Fix-it-first or Up-front Buyer Remedy?

Under a ‘standard’ remedy, notifying parties commit that, within a specified time period following the relevant competition authority’s conditional clearance of a transaction, they will take certain actions to remedy any adverse effect on competition which would otherwise result from that transaction. Importantly, a standard remedy permits the parties to complete the main transaction immediately upon receipt of clearance. The remedy may be a ‘structural’ solution (i.e. a commitment to divest one or more parts of the merged business), a ‘behavioural’ solution (i.e. a commitment to behave – or not to behave – on the market in a certain way, for example in dealings with third parties), or a combination of the two.

Taking the Commission’s process as an example, a typical structural remedy involves a commitment to divest part of the merged business to a purchaser approved by the Commission within a specified period (which may be extended where necessary) following approval of the purchaser by the Commission. If no suitable purchaser is identified within that period, an independent trustee (referred to as a ‘divestment trustee’) is empowered to sell the divestment business at no minimum price – effectively, to conduct a ‘fire sale’. The UK process is very similar.

Under an FiF or UFB remedy – and in contrast to the standard approach – notifying parties commit to suspend completion of the main transaction until they have first entered into binding agreements with one or more third parties (the so-called ‘remedy-taker(s)’) to effect the remedy (i.e. to sell the divestment business, in the case of a structural remedy).[2]

From a competition authority’s perspective, this approach has the advantage of minimising the risks of harm to competition prior to implementation of the remedy, and – more seriously – of a failed remedy. From the merging parties’ perspective, an FiF remedy may also mitigate to some extent the potentially costly risk of having to divest part of the merged business in a fire sale.

FiF and UFB remedies are typically preferable where there is a risk that an appropriate buyer for a divestment business may be difficult to find. This is frequently the case where only a small pool of potential buyers exists, for example when few candidates possess the particular characteristics required by the competition authority to ensure that the business continues to operate as an effective competitor on the market, or where the divestment package comprises a collection of assets to be integrated into an existing business.[3] Various sectors, such as supermarkets, telecommunications and pharmaceutical products – all of which tend to be characterised by relatively high market concentration and barriers to entry – frequently give rise to concerns of this nature.

Both FiF and UFB remedies therefore require the relevant competition authority to review and approve any transactions effecting a remedy (as well as the remedy-taker itself) prior to implementation of the main transaction. The key difference between the two is the point at which this prior approval occurs.

Fix-it-first

In an FiF remedy scenario, notifying parties negotiate and conclude the agreement(s) giving effect to the remedy (e.g. for the sale of a divestment business) before the competition authority has completed its review of the notified transaction, and implementation of the remedy (including the identity of the remedy-taker) is approved at the same time as clearance of the notified transaction is granted. An FiF remedy may be proposed as early as during pre-notification discussions with the authority, and thereafter at any point during the review process, provided there is sufficient time for the authority to assess and approve the proposed purchaser by its decision-making deadline.

An FiF remedy is likely to be particularly attractive where the parties themselves identify significant competition concerns at the outset of a transaction and decide to seek a suitable purchaser for part of the merged business on a pre-emptive basis. Provided the process is commenced sufficiently far in advance, this approach has the advantage of reducing the time pressure under which negotiations with the potential divestment purchaser(s) are conducted, thereby granting the parties increased control over the divestment process.

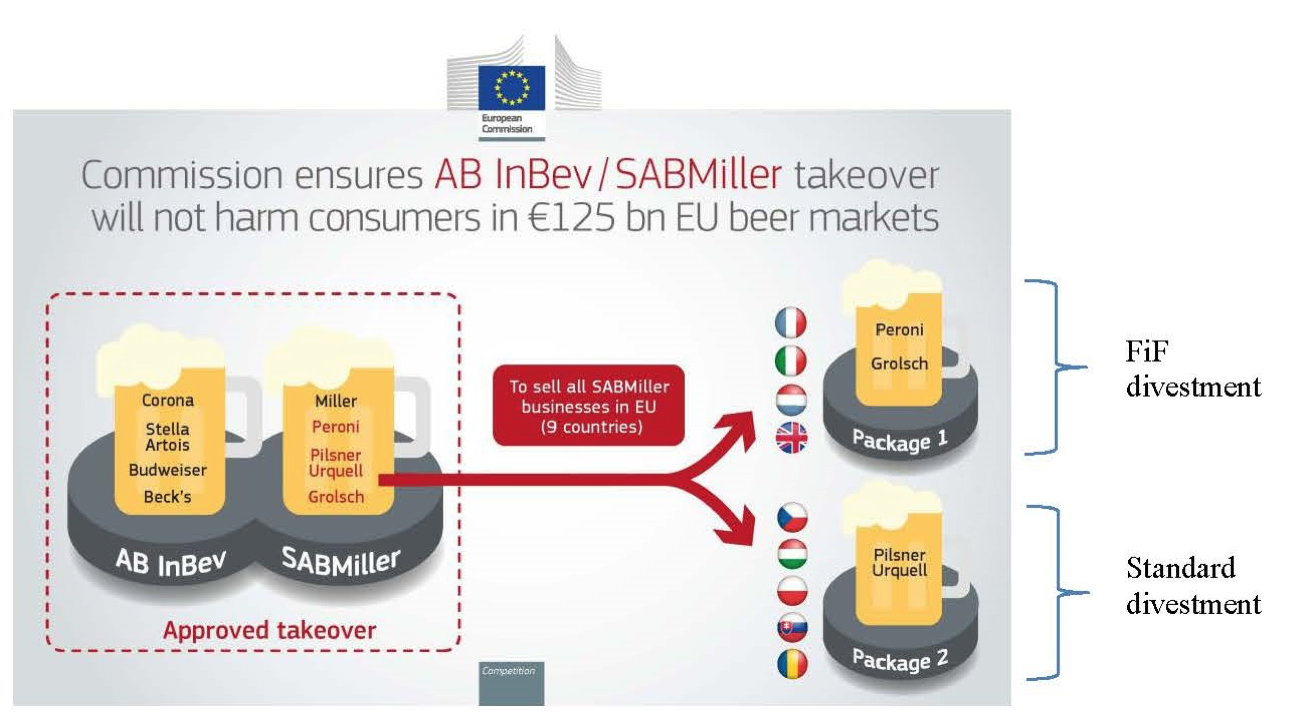

From a competition authority’s perspective, an FiF solution creates a high level of certainty that the agreed remedy will in fact be implemented, but places an increased demand on internal resources, as the assessment of both transactions must be completed in parallel within the review period applicable to the main transaction. Given the complexity of many remedies cases in practice, this may result in negotiation of remedies taking place before a full assessment of the merits of the notified transaction has been undertaken, making an FiF solution inappropriate in cases involving novel theories of harm, new markets and/or in the absence of established decisional practice. Even where this is not the case, negotiation of remedies before a substantive assessment of the notified transaction has been undertaken also creates a risk that the parties may incorrectly assess the scope of the remedies ultimately required to address the authority’s concerns, leading to the use of an FiF solution in combination with other remedies (as in AB InBev / SABMiller[4]), as illustrated by the Commission infographic below.

Source: European Commission

An obvious disadvantage to approaching a competition authority with an FiF solution early in – or even before – the formal merger review process is that in doing so the notifying parties may reduce (or in practice even eliminate) any prospect of avoiding remedies altogether. However, where the likelihood of remedies being required is in any case particularly high, it may make more sense for the merging parties to offer these at an early stage – thereby maximising the time available to reach agreement with the reviewing authority – than to proceed with a protracted and costly review of the transaction as notified. In a less clear-cut situation, an initial attempt to make the case for unconditional clearance does not preclude proposing an FiF solution at a later stage in the process.

Up-front Buyer

In contrast to an FiF scenario, under a UFB remedy the relevant competition authority’s clearance decision does not approve the contractual arrangements giving effect to the remedy proposed by the notifying parties. Instead, the decision is conditional on a commitment from the notifying parties not to implement the main transaction until the competition authority has first approved any agreements required to give effect to those remedies, as well as the identity of any divestment purchaser(s), giving the competition authority more time to approve those arrangements. However, it remains open to the notifying parties to negotiate and conclude agreements with one or more prospective purchasers prior to the authority’s clearance decision.

A clear delineation?

Both FiF and UFB remedy solutions are ultimately intended to ensure that a suitable remedy counterparty is found prior to completion of a notified transaction. Which of these alternatives is used in any given case in practice depends on whether a competition authority’s merger control timetable allows sufficient time to review and approve the relevant contractual arrangements prior to its decision on the main transaction which, in turn, may largely depend on the time taken for notifying parties and remedy-takers to reach commercial agreement. Indeed, the Commission’s guidance on remedies expressly acknowledges that, in situations where a divestment buyer’s identity is crucial to ensure a remedy’s effectiveness, a UFB undertaking will generally be considered “equivalent and acceptable” to an FiF solution.[8]

This is illustrated by cases in which a proposed FiF solution evolves into a UFB remedy as the deadline for a competition authority to reach its decision on the main transaction draws nearer. One such example is the Commission’s decision in NXP Semiconductors / Freescale Semiconductor,[9] where the parties’ proposed remedy was originally presented as an FiF solution (including an executed sale and purchase agreement in respect of the divestment business). However, completion of the divestment required approval from the U.S. Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which would not be received until after the deadline for the Commission’s clearance decision, preventing the Commission from concluding with sufficient certainty that the remedy would in fact be implemented. The Commission subsequently accepted a remedy substantially identical to the original FiF solution, “essentially transforming [the FiF solution] into an up-front buyer remedy”.[10] This meant that a further divestment purchaser approval process was conducted by the Commission following its conditional clearance of the main transaction.

‘Hybrid’ and ‘mixed’ UFB/FiF remedies may also be agreed between notifying parties and competition authorities. An example of the latter is Holcim’s acquisition of Lafarge,[11] where some parts of the divestment assets were subject to a UFB remedy, requiring the Commission to approve the identity of one or more majority ‘anchor’ investors, with the remaining, minority shareholding in the relevant portion of the divestment business to be sold via an initial public offering or spin-off. Other parts of the divestment assets were already subject to a binding sales agreement prior to adoption of the Commission’s decision, which therefore approved the identity of the FiF remedy-taker for those assets.

In a ‘hybrid’ scenario, notifying parties may agree the identity of a potential purchaser with a competition authority prior to its decision on the main transaction (approval of the main transaction being formally granted with the conditional clearance decision), but with approval of the contractual arrangements giving effect to the remedy withheld until after a decision on the main transaction is adopted. This scenario is most likely to arise in relation to remedies which are particularly novel or complex, such that the competition authority feels it needs more time to review and approve the underlying contractual arrangements. This was the case in GE / Alstom,[12] where the Commission noted upon adoption of its conditional clearance that:

“Ansaldo [i.e. the remedy-taker] is an existing competitor in the heavy duty gas turbine market. It already has know-how, experience and an efficient factory for gas turbines and other power plant components… The commitments offered by GE will allow the purchaser to replicate Alstom’s previous role in the market thereby maintaining effective competition.”

Nonetheless, GE was permitted to implement its acquisition of Alstom only after the Commission had formally assessed and approved the finalised divestiture to Ansaldo.

Break-up bid – a third way?

In a break-up bid scenario, it is agreed in advance that immediately following the acquisition of a target business (or at least very shortly thereafter), part of that business will be on-sold to a second acquirer.

A break-up bid may provide merging parties with an attractive alternative to an FiF or a UFB remedy solution by limiting the relevant competition authority’s involvement in selecting a buyer for the divestment business and avoiding any impairment of the parties’ bargaining strength while negotiating the sale. The Commission and the CMA will ‘look through’ the initial acquisition of the target business to the ultimate acquisition of control, provided there is sufficient certainty as to the eventual outcome. This is most likely to be the case where back-to-back agreements are concluded for the transfer of the target to an initial buyer, and for the on-sale of a portion of the target business to a second buyer shortly thereafter.

Where significant competition concerns are anticipated, merging parties may well consider a break-up bid structure to be more appealing than an FiF remedy, as the acquisition of the hived-off portion of the target business may only be assessed according to the usual legal test for identifying competition concerns, rather than by reference to the authority’s standard (and potentially enhanced) purchaser suitability criteria. However, this benefit will only materialise where the parties correctly predict the scope of the divestment remedy likely to be required to address the authority’s concerns.

Conclusion

Despite statements by authority officials that FiF and UFB remedies are relatively exceptional,[13] there is a general upward trend in both the EU and UK. These types of remedy are notably more common in the U.S., but are also seen elsewhere, such as in France.

Their use is no doubt driven in many instances by the parties’ desire for greater control over the outcome of merger review processes. However, it is also likely to be motivated by competition authorities’ desire for greater certainty of outcome, particularly as many industries become more concentrated and the pool of potential buyers for sizeable businesses shrinks over time, and for a more sophisticated approach to merger control remedies and increased dialogue between parties.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

[1] A UFB undertaking was used in over 80% of U.S. merger cases involving structural remedies over the period 2014-2015. Statistics on the use of FiF remedies in U.S. merger cases are not readily available, as unconditional clearance may be granted following the U.S. ‘second request’ process without any public disclosure. Where merging parties propose a FiF solution and the relevant U.S. agency still requires a consent order, the order may refer to the fact that an FiF remedy has been agreed (as in Reynolds American, Inc./Lorillard Inc.) but does not necessarily do so.

[2] UFB provisions may also be used in non-divestment remedies; for example, wholesale access remedies have been subject to UFB undertakings (as in M.6497 Hutchison 3G Austria / Orange Austria¸ on which one of the authors advised Orange Austria).

[3] Standard divestment buyer suitability criteria typically require that the buyer be unconnected to the merging parties and have the financial resources, expertise, incentive and ability to maintain the divestment business, and that the divestment itself should not raise any new substantive competition concerns. These criteria may be supplemented by specific additional criteria on a case-by-case basis.

[4] M.7881 AB InBev / SABMiller.

[5] One of the authors advised VimpelCom Ltd in relation to the joint venture with CK Hutchison Holdings Limited.

[6] One of the authors advised Tullett Prebon plc in relation to its acquisition of ICAP plc’s global broking business.

[7] Interim measures in the form of undertakings rather than orders are also a common feature of UK phase 2 merger reviews, as in the recent Ladbrokes plc / Gala Coral Group Limited case.

[8] Commission notice on remedies acceptable under Council Regulation (EC) No 139/2004 and under Commission Regulation (EC) No 802/2004 (2008/C 267/01), para. 57.

[9] M.7585 NXP Semiconductors / Freescale Semiconductor. In GE / Alstom, a divestment buyer was identified during the EC’s review but a sale agreement was not signed at that stage. The agreed commitments therefore contained an UFB provision to prevent the parties from implementing the notified deal until the buyer was officially approved following a separate review conducted after adoption of the conditional clearance decision.

[10] Ibid, para. 200.

[11] M.7252 Holcim / Lafarge.

[12] M.7278 General Electric / Alstom (Thermal Power – Renewable Power & Grid Business).

[13] See speech by Carles Esteva Mosso, Deputy Director General for Mergers at the Commission, to the 19th IBA Annual Competition Conference, Florence, 11 September 2015.

Featured News

BHP Unveils £31bn Mining Megamerger Proposal with Anglo American

Apr 25, 2024 by

nhoch@pymnts.com

ByteDance Prefers Shutdown Over Sale of TikTok Amid US Ban Threats

Apr 25, 2024 by

CPI

FCC Votes to Restore Net Neutrality Rules

Apr 25, 2024 by

nhoch@pymnts.com

Apple Rejects Spotify’s Updated App Over In-App Pricing Disclosure

Apr 25, 2024 by

CPI

FCC Set to Reinstate Net Neutrality Rules Today

Apr 25, 2024 by

CPI

Antitrust Mix by CPI

Antitrust Chronicle® – Economics of Criminal Antitrust

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

Navigating Economic Expert Work in Criminal Antitrust Litigation

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

The Increased Importance of Economics in Cartel Cases

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

A Law and Economics Analysis of the Antitrust Treatment of Physician Collective Price Agreements

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

Information Exchange In Criminal Antitrust Cases: How Economic Testimony Can Tip The Scales

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI