Canadian Competition Law Reform: A Diagnosis and Proposals for Reform of Canada’s Ineffective Merger Notification Rules

February 2018

Canadian Competition Law Reform: A Diagnosis and Proposals for Reform of Canada’s Ineffective Merger Notification Rules

By David Rosner1

Introduction

Canada’s Competition Act (the “Act”), like competition laws in many other jurisdictions, contains merger notification rules. Put simply, these rules require that where parties to a M&A transaction exceed specified economic thresholds, the parties must notify Canada’s competition agency, the Competition Bureau (the “CCB”), prior to closing. The rules’ main purpose is to ensure the CCB is notified of, and given time to review, those M&A transactions deemed most likely to give rise to potential harm to competition.

Canada’s merger notification rules were originally implemented in 1986, and have been largely unchanged ever since. Canada’s rules predate the implementation of merger notification rules in most other mature economies around the world (except for the United States). There has never been a broad discussion in Canada about whether the rules are or remain effective at accomplishing their underlying policy objective, or whether reform is desirable. The absence of such discussion – or reform – over such a long time frame is out of step with experiences in other mature economies (where such discussions and reform have occurred),2 and inconsistent with the recommended best practices of leading international organizations (to which Canada belongs).3

In fact, such a broad discussion about the effectiveness of Canada’s merger notification rules, and eventual reform of the rules, is long overdue. This is because the Canadian merger notification rules are ineffective at accomplishing their main policy objective of requiring M&A transactions that are most likely to give rise to potential harm to be notified. The rules are also ineffective at accomplishing numerous secondary objectives.

Section I of this paper identifies the main and two key secondary policy objectives of Canada’s merger notification rules. The remainder of the paper explains why the current merger notification rules are ineffective at accomplishing these objectives.

- First, Section II demonstrates how the rules’ economic thresholds result in the CCB being notified of many M&A transactions that do not have a significant potential for harm, while many M&A transactions that do have a significant potential for harm are not subject to notification. The economic thresholds are therefore ineffective at accomplishing the main policy objective of ensuring the notification of M&A transactions that have the most significant potential for harm.

- Second, Section III demonstrates how the merger notification rules have different results depending upon the transacting parties’ organizational structure and the M&A transaction structure itself. Among other things, the rules permit avoidance. The merger notification rules therefore do not meet the objective of being “transaction neutral.”

- Third, Section IV explains why failure to notify a M&A transaction where the economic thresholds are exceeded (i.e., a “failure to file”) is very unlikely to be sanctioned in Canada. The merger notification rules therefore do not meet the objective of being effectively enforceable.

A full-scale proposal for reform of Canada’s merger notification rules requires is beyond the scope of this paper, since such a proposal must be proceeded by a broad discussion within the Canadian competition law community.4 However, this paper sets out proposals for how the rules should be reformed to remedy aspects of their ineffectiveness, and all of these proposals would be commendable components of a full-scale proposal for reform.

A broad discussion about the effectiveness of Canada’s merger notification rules is in the interests of all stakeholders. Such a discussion, if it results in reform, would enable the CCB to concentrate on the review of (and protect Canadians from) M&A transactions that have the most significant potential for harm to competition, and permit firms contemplating M&A to plan their transactions in a more predictable manner. Such a discussion should be facilitated by the CCB, and in due course the government of Canada should include reform of the merger notification rules among its political priorities.5

History and Policy Objectives of Canada’s Merger Notification Rules

As early as 1969, policy makers in Canada recognized that ex post regulation of conduct that harmed competition was insufficient to prevent against all forms of competitive harm. In particular, ex post regulation did not offer enforcers tools to prevent independent firms – especially in cases where the firms did not previously possess market power – from entering into M&A transactions that would create, and permit the exercise post-merger of, market power.6

These early policy makers recommended, among other things, that a government-established body “keep itself fully informed of merger activity… to facilitate the examination of those [mergers] that appeared to contain a significant potential for harm.” Being “fully informed of merger activity” would, however, entail an extraordinary amount of work by the government body due to the large number of M&A transactions that occur. However, the volume of work could be made manageable through “a process of selection. It would be essential that this process ensure timely consideration of all mergers in which there was a significant potential for harm. Appropriate procedures should be initiated to accomplish this objective in a regular and comprehensive way.”7 The main objective of merger notification rules was thus articulated: selecting those M&A transactions for which there is a significant potential for harm to competition in Canada for notification. Other M&A transactions – that is, those that are smaller or have less nexus to Canada – are permitted to proceed without notification (or other process).

Despite the recognized need for the introduction of merger control (and notification) rules, reform to Canada’s competition laws did not occur for some time.8 Only in the 1980s was the bill that would ultimately result in the passage of the Act (including the merger notification rules) introduced. The government accompanied that bill with other publications that shed light upon some of the secondary objectives of the proposed merger notification rules. One publication explained that the merger notification rules needed to be “transaction neutral”, which was to ensure “that transactions will not be restructured so as to avoid the requirements to prenotify.”9 Another publication explained that that merger notification rules needed to be “both enforceable and effective”, noting that “the law has to be well articulated and based on clear and realistic standards that can be readily understood by the business community and the courts.”10

The Act, including the merger notification rules, was passed into law in 1986. While the Act has been subject to some updating,11 the merger notification rules have remained largely unchanged, and have not been subject to extensive public discussion.

This brief history of the merger notification rules in Canada reveals one main and at least two important secondary public policy objectives that the rules were intended to accomplish.

- First, the main objective of the merger notification rules is to “select” those “mergers in which there [is] a significant potential for harm” to competition in Canada for notification to the CCB. The Act pursues this objective through the establishment of economic thresholds that are a proxy for the nexus a transaction must have to Canada before it is deemed to have the required significance for notification. Parties to M&A transactions that surpass these economic thresholds must notify the CCB prior to closing.

- Second, a secondary objective of the merger notification rules is that they operate in “a regular and comprehensive way,” or in other words, be “transaction neutral.” The Act pursues this objective through the establishment of different notification rules intended to apply to various types of M&A transaction structures.

- Third, another secondary objective of the merger notification rules is that the rules be “enforceable” by courts. The Act pursues this objective through the establishment of a criminal offence for certain failures to notify.

All of these public policy objectives were and remain valid. Their validity is evidenced by the merger notification rules that have been enacted around the world in the past 30 years, almost all of which pursue the same or similar objectives.12 However, as discussed below, the failure to revisit the merger notification rules for more than 30 years in Canada – a period far longer than most jurisdictions, who update their merger notification rules more frequently – has permitted a disconnect to arise between these objectives and the operation of the rules themselves, such that the rules are now ineffective at achieving their important objectives.13

Ineffectiveness of The Economic Thresholds

In pursuit of the objective of selecting for notification those M&A transactions most likely to result in potential harm to competition in Canada, the Act establishes two economic thresholds; M&A transactions whose aspects surpass both of these economic thresholds must be notified to the CCB prior to closing.14 Roughly stated, the thresholds are as follows:

- The Size-of-Parties Threshold. To exceed the Size-of-Parties threshold, the parties to the transaction must have on a combined basis either (i) assets in Canada whose book value exceeds $400 million or (ii) gross revenues from sales in, from or into Canada in their last financial year whose book value exceeds $400 million. In applying this threshold, the assets and revenues of the parties’ affiliates must also be taken into account; this results in the value of the vendor’s assets and revenues being counted (where the target is majority owned by a single vendor or there is an asset acquisition).

- The Size-of-Target threshold. To exceed the Size-of-Target threshold, the target / acquired business must have either (i) assets in Canada whose book value exceeds $88 million or (ii) assets in Canada that generated gross revenues from sales (whether made to customers in Canada (domestic sales) or to customers outside Canada (export sales)) whose book value exceeds $88 million.15 The Size-of-Target threshold is adjusted annually according to changes in nominal gross domestic product. In applying this threshold, there is inconsistency as to whether the assets and revenues of the target business’ subsidiaries must be taken into account, depending on whether the target is a corporation or some other type of entity.16

- Developments Over the Past 30 Years

The economic thresholds reflect an attempt to identify those M&A transactions most likely to result in potential harm to competition in Canada, but were crafted to pursue this objective in the context of the Canadian economy as it stood in 1985. There have been significant developments to the economy and the CCB has gained extensive experienced administering the merger notification rules in the intervening 30 years. The substance of these developments and the learning both suggest that the economic thresholds designed long ago are no longer fit for purpose. In particular:

- Increase in Imports from Trade. In 1985, Canada had no free trade agreements. Canada signed its first free trade agreement with the United States in 1987, and since that time has entered into a plethora of others, including most recently with the European Union.17 In addition, Canada became a member of the World Trade Organization upon its foundation in 1995, which subsequently admitted countries that export large volumes of goods (such as China in 2001 and Vietnam in 2007). These agreements and memberships (i) permitted international firms to compete without restriction or subject to fewer and lower tariffs in Canada, (ii) facilitated extensive cross-border M&A, and (iii) permitted firms to rationalize production in the most efficient regions. These changes to the economy have resulted in the value of imports into Canada more than quadrupling between 1985 and 2016. Similarly, the value of imports as a share of Canadian GDP has increased from 20.6% of GDP in 1985 to 32.3% of GDP in 2016.18 The share that imports represent of the Canadian economy is likely only to grow as Canada enters into additional free trade agreements and as the economy shifts toward new industries (in particular, knowledge economy industries) that operate across borders, which are discussed below.

- Sectoral Changes to the Economy. In 1985, Canada’s economy was heavily weighted to the manufacturing and natural resources sectors. However, the past 30 years have seen numerous industrial and technological developments that have altered the sectoral composition of the economy (in Canada and elsewhere). One sector that has increased significantly is services, which represented almost 31% of Canadian GDP in 2016; this is an increase in share of more than 27% since 1997 (and by even more since 1985). By contrast, the share of Canadian GDP represented by the energy sector has fallen by more than 20% compared to 1997 levels (and by even more since 1985), and manufacturing’s share of GDP has fallen by almost 30% from 1997 to 2016.19 These changes show how industries that have significant asset bases (such as energy and manufacturing) are significantly smaller components of the Canadian economy than they were 30 years ago, and that industries that do not require significant asset bases to operate (in particular, the services industry) are significantly larger components of the Canadian economy. The share that service industries represent of the Canadian economy is likely only to grow as technology advances and more industries take to the “cloud” (disconnecting the location of their physical assets from their commercial efforts).20

- Experience of the CCB. In 1985, the CCB did not yet exist and no mergers had yet been notified in Canada. Since that time the CCB has reviewed thousands of notifications, including more than 200 notifications per year over the last ten years.21 Given this extensive experience, the CCB will have a sophisticated view as to whether the economic thresholds are effective. However, the government is not known to have solicited the CCB about whether the economic thresholds remain effective. In addition, some of the CCB’s actions suggest that the CCB (at a minimum) may believe that the economic thresholds are under-broad, in that they fail to require notification of certain transactions that have the potential to harm competition.22

In addition to these industrial developments and learnings, an examination of the CCB’s work and the economic thresholds themselves indicate that the thresholds are now poor identifiers of those M&A transactions that have the most significant potential for harm. Instead of accomplishing their main objective, the economic thresholds (i) result in the notification of large numbers of transactions that are unlikely to harm competition, and (ii) often do not require the notification of transactions involving at least one non-Canadian party that have the potential to impact competition in Canada significantly. In other words, the economic thresholds result in the rules being both over- and under-broad. These unintended aspects of the economic thresholds should be reformed, so that the CCB is notified of, and is able to dedicate its reviewing resources to, those M&A transactions that are most likely to have significant potential for competitive harm.

- Over-Broad Nature of the Economic Thresholds

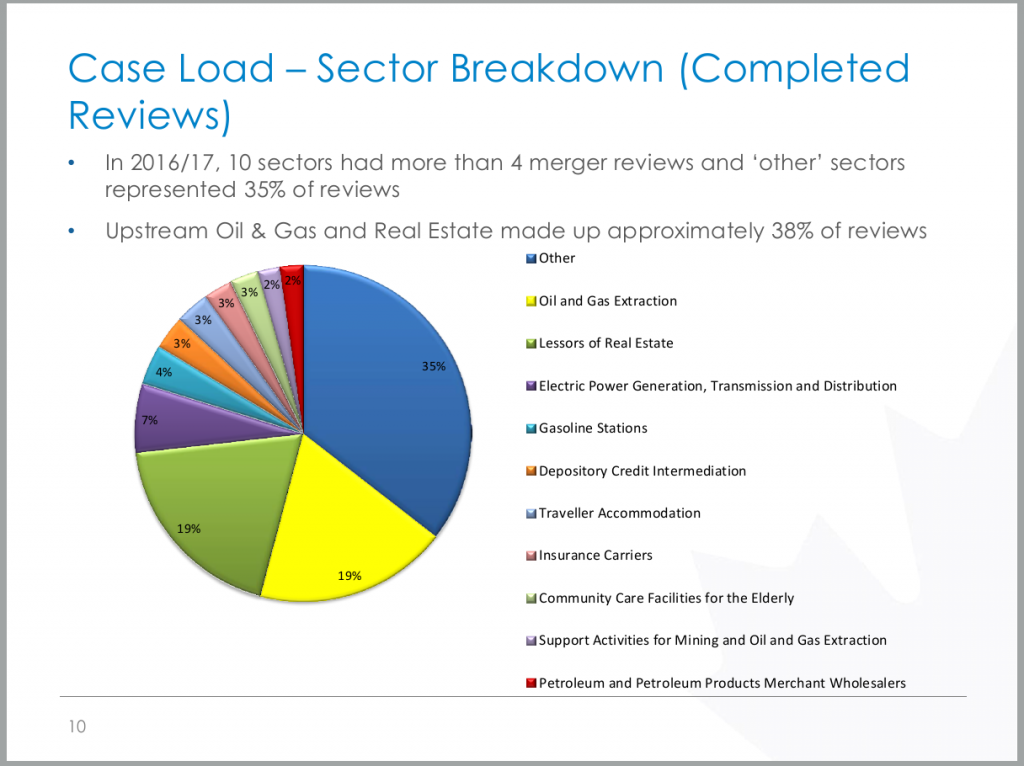

One significant reason why the rules are over-broad – in that they require notification of many transactions that are not likely to cause potential harm – is that the economic thresholds assess the value of the parties’ revenues and assets in Canada. The economic thresholds thus assume that the competitive significance of assets and revenue are broadly similar. However, the CCB’s experience indicates that this assumption may not be valid, and in particular that many M&A transactions that are subject to notification due to the significant value of the parties’ assets (but where similarly large revenues are not earned by the transacting parties) are very unlikely to harm competition. This experience is observable through statistics published by the CCB, which show that a large number of notifications originate from sectors that involve large asset bases (i.e., the Oil & Gas and Real Estate sectors represented 38% of the CCB’s notifications in 2016).

Figure 1 – CCB 2016 Notifications – Industry Breakdown23

Despite the large numbers of notifications that occur in these asset-intensive sectors, M&A transactions in these sectors are very unlikely to harm competition. For example, many transactions in the Oil & Gas sector involve the sale of natural resource assets. Such assets often have significant book values (e.g., proven reserves of oil that are very valuable), but have little economic significance because the assets are not currently producing (and may never produce, depending upon economic conditions). A similar dynamic exists in the Real Estate sector, where M&A transactions often involve the sale of assets of significant book value that have a comparatively small revenue generating capacity (i.e., the annual rent is modest compared to the present value of the building (including its underlying real estate)). The large book values of assets involved in M&A transactions in these two sectors frequently results in such transactions becoming notifiable, but the CCB has never challenged a transaction in either sector, evidencing how unlikely it is that such transactions might potentially harm competition.24

Given the unlikeliness that transactions in these asset-intensive sectors will result in potential harm to competition, there is no identifiable enforcement benefit to requiring the frequent notification of transactions in these types of sectors.

Proposal 1: Absent evidence that there is a material number of transactions that exceed the notification thresholds exclusively due to the operation of the “assets” component and which are likely to give rise to potential harm to competition, the “assets” component of the economic thresholds should be eliminated. The only exception is with respect to new joint ventures, where the value of assets to be contributed to the joint venture may remain an important way to identify those M&A transactions involving joint ventures that are most likely to have significant potential for harm. See Section III.4, below, regarding the application of merger notification rules to joint ventures.

A second reason why the rules are over-broad is that the Size-of-Parties threshold requires that the assets and revenues of the vendor be counted in many cases. This occurs where, for example, a vendor owns more than 50% of a corporate target, the target is a partnership (so long as the vendor is conveying a sufficient percentage of the partnership’s interests), or the target is an asset. In the past 30 years, it has become commonly understood that a vendor does not merge with the purchaser, and so information about the vendor is unlikely to assist in identifying mergers that might result in potential harm. This common understanding is reflected in international best practices, which recommend against applying economic thresholds to vendors.25

Example 1: Corporation 1 controls Corporation 2 and Corporation 3. Corporation 2 and Corporation 3 each have revenues from their Canadian assets of $100 million. Corporation 1 agrees to sell Corporation 2 (but not Corporation 3) to Corporation 4. Corporation 4 has revenues in Canada of $250 million. The proposed transaction is notifiable because the value of Corporation 2, 3 and 4’s revenues in Canada on a combined basis exceeds the Size-of-Parties threshold (and Corporation 2’s revenues exceed the Size-of-Target threshold). Even though Corporation 3 is not being sold, its revenues must be counted for the purposes of the Size-of-Parties threshold because it is affiliated with Corporation 2 on a pre-transaction basis.

Proposal 2: The Size-of-Parties threshold should apply only to the merging parties (that is, the purchaser and the target).26 The Size-of-Parties threshold should not apply to the vendor (or any other third party that is not merging as a result of the M&A transaction). Information about the vendor is only relevant to merger notification questions where the vendor is not selling all of the target business, but will continue to retain a significant interest (such that the target business becomes a joint venture, and the vendor is a party to the merger with the purchaser).

A third reason why the rules are over-broad is that the Size-of-Target threshold is only applied to the target of a transaction. This results in acquisitions of large Canadian companies by acquirers without a presence in Canada being subject to notification, even though such transactions are very unlikely to give rise to potential harm (given that the acquirer has no Canadian business). Such M&A transactions, where only one party has a significant commercial presence in Canada, have little nexus to Canada. The unlikelihood of such M&A transactions impacting competition (and the corresponding lack of need for notification) is recognized in international best practices, which recommend that the determination of a M&A transaction’s nexus to a jurisdiction be made on the basis that at least two parties to the M&A transaction have a significant connection to the jurisdiction.27 It is also notable that requiring notification of such M&A transactions is not “transaction neutral,” since an acquisition by the same large Canadian company of the same non-Canadian acquirer that did not have a presence in Canada would not be notifiable.

Proposal 3: The Size-of-Target threshold should apply to at least two parties to the merger (i.e., not the vendor or any other third party that is not merging as a result of the transaction). Alternatively, there should be another threshold to ensure that at least two parties have significant business in Canada, thus establishing a nexus between the merger and Canada (as opposed to a nexus between only one party and Canada). However, the reformed rule should not operate in a manner to cause new joint ventures that will not have a nexus to Canada to become subject to notification. See Section III.4, below, regarding the application of merger notification rules to joint ventures. Applying the Size-of-Target threshold to at least two parties to the merger would also address the fact that, at present, the threshold is not transaction neutral.28

- Under-Broad Nature of the Economic Thresholds

One significant reason why the rules are under-broad – in that transactions that might result in potential harm are not subject to notification – is that the economic thresholds are focused on economic activity originating in Canada as opposed to economic activity whose effect occurs in Canada. In particular, the Size-of-Target threshold assesses, among other things, the value of revenues that a target generated from its Canadian assets. This is a measure of the sales by the target’s Canadian assets to customers in Canada (i.e., domestic sales) and to customers outside of Canada (i.e., export sales). Excluded are sales by a target’s non-Canadian assets to customers in Canada (i.e., import sales). The Size-of-Target threshold therefore assumes the competitive insignificance of commercial activity occurring in Canada that originated from outside Canada. There are numerous problems with this assumption, and more generally with the exclusion of import sales from the application of the Size-of-Target threshold.

- First, the assumption is likely outdated (if it was ever correct) given changes to the Canadian economy in the past 30 years. As described above, the economy is now far more weighted to imports (i.e., economic activity that originates from outside Canada) and new industries that can perform economic activity from wherever their assets are located.

- Second, the assumption is inconsistent with the operation of the Size-of-Parties threshold, which takes import sales into account (and therefore deems the value of such imports to be of at least some significance for policy purposes).

- Third, the assumption implicitly outsources the review of transactions among non-Canadian firms that have significant sales into Canada to competition law agencies outside of Canada. Of course, those foreign agencies have no mandate to protect competition in Canada.

For these reasons, the assumption must be incorrect. Instead, all sales made by merging parties to customers in Canada (wherever the assets associated with those sales originate) have an economic nexus to Canada, and the potential to harm that transactions among such parties creates is the same regardless of how the sales to Canadian customers are classified. If it were asked, the CCB may well agree with this position: subjecting economic activities originating from outside of Canada to the economic thresholds appears to have been one of the key goals of IG#15, which put forward an aggressive interpretation of whether, among other things, sales to customers in Canada should be classified as import or domestic; as noted above, IG#15 was not adopted.29

Proposal 4: The “revenue” component of the Size-of-Target threshold should be extended to include sales “into” Canada by merging firms’ non-Canadian affiliates. Such “import” sales have clear economic significance in and nexus to Canada, and there are no obvious policy reasons (such as comity) to exclude such revenues from the application of the Size-of-Target threshold.

- Process for Reforming Economic Thresholds to be Based on Facts

The over- and under-broad nature of the economic thresholds reveals how Canada is past due for a broader discussion of whether they continue to serve the main policy objective of the merger notification rules. When this discussion occurs, it must be informed by factual information. At present, however, there is little data or other objective information that would permit a detailed study of how economic thresholds could be better formulated to achieve their intended purpose. If the economic thresholds are to be maintained and refined, better information is required for their calibration than presently exists.

Proposal 5: At present, the Canadian notification form does not require that any direct information be provided to evidence how and why the economic thresholds are surpassed. The notification form should be amended to require that filers provide basic economic information about their Canadian businesses. This type of information is collected in the notifications of other forms in other jurisdictions, so should not be burdensome to collect in Canada.30 In addition, this information is likely already at hand, as parties were required to collect it for the purposes of determining whether or not they exceeded the economic thresholds. Examples of information that should be collected include the value of a filer’s assets in Canada and its Canadian sales (broken down by “in” / domestic, “from” / export and “into” / import categories). Such amendments to the form would permit the collection of data to assess the economic reasons why different types of transactions become notifiable, and what the effect of changing the economic thresholds might be on the mix of transactions that are subject to notification.

Rules are Not Actually Transaction Neutral

In pursuit of the objective of the merger notification rules operating in a “regular and comprehensive way” and being “transaction neutral,” the Act contains a complex set of notification rules intended to apply to various transaction structures. However, 30 years of experience with the rules has revealed problems and gaps, the operation of which reveals that the rules are not in fact transaction neutral. In addition to not being transaction neutral, these problems and gaps (i) permit parties to structure their transactions around the notification obligation (i.e., avoidance) and (ii) often require notification of transactions that have no competitive effect (i.e., corporate reorganizations).

The fact that the merger notification rules are not transaction neutral is observable from recent filings made by the CCB in respect of the merger of The Dow Chemical Company (“Dow”) and E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company (“DuPont”). As global scale companies, the merger was subject to notification in multiple jurisdictions, including the United States, the European Union, China and Brazil. However, the merger was not subject to notification in Canada despite the very significant local assets and sales of each merging party. The lack of a Canadian notification was due to the transaction structure selected by the parties (i.e., a new independent entity that would amalgamate with each of Dow and DuPont upon closing, and neither of these transactions were individually notifiable under the merger notification rules’ amalgamation provisions). The CCB did not receive notification of the transaction; instead, it was obligated to recognize the competitive significance of the transaction and conduct a review on its own initiative (without the benefit of the processes contained in the Act to facilitate such reviews, such as the right to receive certain information in a notification form and the ability to compel the production of information through a supplementary information request). In court filings seeking the mandatory production of information to assist its review, the CCB explained that “Notwithstanding the complexity and size of the Parties’ businesses and the Proposed Transaction, due to its unusual structure, the Proposed Transaction is not notifiable under section 114 of the Act… This means that the Commissioner did not automatically receive detailed information regarding the Parties’ businesses in order to conduct his review, as would be typical in other transactions of this size and complexity…”31 Obtaining this basic information required the CCB to expend resources. The significance of this merger for competition in Canada was borne out by the fact that the CCB ultimately demanded, and the parties agreed to, remedies to address the CCB’s concerns about the merger’s impact on competition in Canada in a number of markets.32 If this transaction had been structured differently, a notification would have been required.

This section describes a foundational reason why the rules are avoidable, as well as select examples of the technical problems and gaps with the merger notification rules. Collectively, these issues demonstrate the merger notification rules do not meet their objective of being transaction neutral.

- No Anti-Avoidance Rules

As described herein, there are numerous methods to structure around the merger notification rules. All of these methods (and many others) are available to parties because the Act contains no anti-avoidance provisions. This is in contrast to merger notification rules in other jurisdictions33 and other regulatory schemes in Canada, 34 which contain sensible anti-avoidance provisions. If the merger notification rules are to be “transaction neutral”, it is important to maintain an anti-avoidance provision so that the operation of the merger notification rules cannot be defeated through purely technical means.

Proposal 6: The merger notification rules should contain a broad anti-avoidance rule.

- Different Affiliation Rules for Different Types of Entities

At present, the Act creates different “affiliation” rules for different types of entities (e.g., corporations and non-corporate entities such as partnerships). These differences sometimes permit transactions that would otherwise be subject to notification to be structured in a manner that avoids notification (whether for avoidance purposes or not). Conversely, these differences also sometimes operate to require that corporate reorganizations be notified to the CCB, even though such transactions can have no competitive effect and the Act attempts (unsuccessfully) to exempt such transactions from notification.35 Set out below are situations that arise under the Act, and which demonstrate how the differing affiliation rules undermine the objective of the merger notification rules operating in a transaction neutral manner.

Example 2: Partnership 1 holds all the interests of Partnership 2, which holds all the intrests of Partnership 3. Partnership 3 operates a Canadian business with $1 billion of revenues. Due to gaps in the affiliation rules, Partnership 1 and Partnership 3 are not “affiliates” under the Act. Partnership 1 agrees to acquire Corporation 4, which operates a Canadian business with $100 million of revenues. The proposed transaction is not subject to notification under the Act because on a combined basis, Partnership 1 and the Corporation 4 (together with their “affiliates”) do not have revenues in Canada whose value exceeds the Size-of-Parties threshold.36 By contrast, if Partnership 1 and Partnership 3 were corporations, “Corporation 1” and “Corporation 3” would be affiliates (and the assets and revenues of “Corporation 3” would be counted for the purposes of the Size-of-Parties, thus surpassing the threshold) and a notification would be required.

Example 3: Corporation 1 owns all the interests of Partnership 2, which owns all the interests of Partnership 3, which operates a Canadian business with $1 billion of revenues. Due to gaps in the affiliation rules, Corporation 1 and Partnership 2 are not “affiliates” under the Act. In a corporate re-organization, Corporation 1 wishes to wind up Partnership 2 and hold the interests of Partnership 3 directly. Partnership 2 agrees to convey all its interests in Partnership 3 to Corporation 1. The proposed transaction is subject to notification under the Act. By contrast, if Partnership 2 and Partnership 3 were corporations, “Corporation 1” and “Corporation 2” would be affiliates and the corporation reorganization would be exempt from notification.

The Canadian government has responded to these long-standing problems in the affiliation rules by introducing a bill in Canada’s Parliament; at the time of writing, this bill (known as C-25) continues to be subject to debate.37 Regardless of whether or not it is ultimately passed, however, the reforms contained in Bill C-25 are inadequate. This is so because instead of simply doing away with the distinctions about how different types of entities are affiliated under the Act, the bill simply creates a new “catch all” category of entity called “entity.” The creation of a new category of entity does not address the underlying problems created by merger notification rules that attempt to provide for every specific type of affiliation relationship.

Proposal 7: The merger notification rules should require the notification of transactions that exceed the economic thresholds regardless of how the merging parties’ organizational structures are established or the transaction is structured. The most effective solution from a policy perspective would be (i) for the purposes of the merger notification rules, to adopt into Canadian law the European Union’s concept of an “undertaking” (or a “single economic entity”), which constitutes a parent entity and every other entity whose autonomy is subordinated to the parent entity, and (ii) to apply the merger notification rules’ economic thresholds to undertakings that are a party to a merger in a consistent manner.

- No Transaction Aggregation Rules

The Act does not require the “aggregation” of multiple transactions between the same counter-parties. This gap in the rules is another reason why the merger notification rules are not transaction neutral and are avoidable. For example, where a single vendor has organized a business within multiple subsidiaries and sells those subsidiaries directly to a single purchaser, there is no obligation to aggregate the value of the target subsidiaries for the purposes of applying the Size-of-Target threshold. If one (or some) but not all of those subsidiaries exceed the Size-of-Target threshold, a notification is required in respect of the sale of that subsidiary, but not the others.38 Similarly, where a vendor has organized a business within one subsidiary, the vendor may break up its business into multiple subsidiaries (none of which exceed the Size-of-Target threshold) and sell each of them to a purchaser without notifying the CCB. The lack of transaction aggregation rules in Canada is in contrast with the existence of such rules in other mature economies, including in the United States and European Union.39

Example 4: Corporation 1 owns all of the shares of each of Corporation 2, Corporation 3 and Corporation 4. Each of Corporations 2, 3 and 4 each have businesses in Canada with revenues of $50 million. Corporation 5 agrees to acquire each of Corporations 2, 3 and 4 from Corporation 1 pursuant to a single transaction agreement. The proposed transaction is not subject to notification because Size-of-Target threshold applies to the acquisition of each corporation separately, and none of the corporations on an individual basis have sufficient revenue to surpass the Size-of-Target threshold. The merger notification rules do not contain any requirement that the transactions be aggregated in some manner for the purposes of applying the Size-of-Target threshold (or any method by which to conduct such aggregation). By contrast, if Corporation 1 held the businesses held by Corporations 2, 3 and 4 directly (as opposed to through intermediate corporations), the sale of these businesses would constitute an asset acquisition that surpassed the Size-of-Target threshold. That said, it would be open to Corporation 1 pre-transaction to split the businesses into multiple corporations, for the purposes of avoiding the notification obligation.

Proposal 8: The merger notification rules should require that where the same counter-parties engage in multiple transactions within a defined time period, the value of transferred businesses should be aggregated for the purposes of applying the Size-of-Target threshold. The merger notification rules should also provide a method for conducting such aggregation.40

- Problems with The Joint Venture Exemption

The Act contains a broad exemption from notification for the formation of joint ventures, but only if the joint ventures operate in non-corporate form.41 The fact that the exemption applies only to joint ventures in non-corporate form (as opposed to those conducted through a corporate entity) demonstrates how the exemption is not transaction neutral. There is no competition policy reason for exempting some joint ventures but not others based on the type of organization through which the joint venture conducts its business.

Proposal 9: The joint venture exception from notification should operate regardless of the organizational structure utilized by the joint venture partners (i.e., be transaction neutral).

Tangential to the question of transaction neutrality but related to the issue of whether the merger notification rules are under-broad, it is notable that the joint venture exemption is very broad. In particular, joint ventures are exempt from notification where only three conditions are satisfied. First, the joint venture must be in non-corporate form (which, as noted above, is not transaction neutral). Second, the parties to the joint venture must be parties to an agreement in writing that (a) obligates at least one party to contribute assets to the joint venture, (b) governs the relationship between the parties, (c) restricts the range of activities in which the joint venture engages, and (d) allows for the orderly termination of the joint venture. Third, the joint venture cannot result in any change of control over the parties to the joint venture (but not the joint venture itself). Practically speaking, the formation of any type of joint venture is capable of being fit into this exemption, and this exemption is far broader than the limited policy purpose intended to be served by the exemption, which was for the creation of new joint ventures that “would not reasonably have taken place … in the absence of the combination because of the risks involved in relation to the project or program and the business to which it relates…42

Example 5: Corporation 1 and Corporation 2 each have long-established operating businesses that each have $1 billion of revenues and assets in Canada. Corporation 1 and Corporation 2 agree to merge their operating businesses by contributing them to a 50-50 joint venture to be operated through a partnership. Corporation 1 and Corporation 2 enter into the requisite written agreement. Although the economic thresholds are satisfied and the transaction will result in a change to market structure that could result in potential harm to competition, the transaction is not subject to notification under the Act because of the operation of the exemption for non-corporate joint ventures.

Proposal 10: The policy objective(s) of the joint venture exception should be discussed and better articulated, and the scope of the exemption should be closely connected to that objective(s).

Rules are Not Effectively Enforceable

In pursuit of the objective of the merger notification rules being “enforceable” by courts, the Act contains a provision that makes “failure to file” a criminal offence. In particular, the Act provides that any person who fails to notify a notifiable transaction “without good and sufficient cause” is guilty of a criminal offence and is liable to a fine of up to $50,000.

However, aspects of the provision make it very unlikely that any person would ever be sanctioned in Canada for a “failure to file.”

- First, the criminal nature of the “failure to file” rule means that the CCB – although charged with administering the merger notification rules – is not capable of enforcing those rules itself. Instead, the CCB must seek the assistance of a prosecutor of the Attorney-General, who is the only person capable of prosecuting a criminal charge.

- Second, the stigma associated with a criminal charge or conviction is significant, and may be disproportionate to the blameworthiness of the parties to the transaction that failed to notify the CCB (even where “good and sufficient cause” does not exist).

- Third, a criminal conviction may not be the remedy the CCB seeks (which may involve putting in place processes to ensure future compliance with the merger notification rules).43

- Fourth, the available sanction (a fine of up to $50,000) is nugatory compared to the value of any transaction that exceeds the economic thresholds. The economic insignificance of this fine is further underlined by the fact that it is the very same size as the applicable filing fee (which is also $50,000). This filing fee is likely to increase to $72,000 in 2018.44 As a result, in the future it will be $22,000 less expensive to fail to file and be subject to criminal sanction than it will be to file a notifiable transaction.

Given these factors, it is perhaps no surprise that 30 years after coming into force, no person has ever been charged or convicted under the “failure to file” provision in the Act.

It should be noted that the CCB has taken the position in public remarks that it can take action in respect of a “failure to file” by bringing an application for a civil order before a specialized court, the Competition Tribunal, using another provision of the Act. That other provision is expressly directed at “gun jumping” – that is, where parties complete a transaction prior to the expiry of the waiting periods. That said, the Bureau has never utilized this other provision in respect of a “failure to file”, and given the existence of an express “failure to file” provision it is doubtful whether the “gun jumping” provision can be used in this manner.

Proposal 11: The “failure to file” rule should be re-written in a number of ways so that it can be effectively enforced. First, failure to file should be subject to civil sanction only (not criminal); this sanction should either be left to Competition Tribunal impose pursuant to a civil order upon application by the CCB. This would avoid having to prove any element of a “failure to file” on the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard or to involve a prosecutor. Second, failure to file should be a matter of absolute or per se liability. The parties’ reason for the failure to file is not relevant to the question of whether the Act has been contravened; instead, such reasons are only relevant to the question of the appropriate penalty or sanction. Third, failure to file should be subject to a maximum monetary penalty and other sanction that is capable of being significant and proportional to the size of the parties to the transaction.

Conclusion

The adequacy of existing merger notification rules for the achievement of their public policy objectives is once again a topic of conversation around the world. It is past time that this conversation migrates to Canada, where the Act’s merger notification rules have been largely unchanged in more than 30 years, even though the economy in which those rules are applied has changed significantly in that time period (and will continue to change going forward). The many ways in which the Act’s merger notification rules are ineffective are clear to both practitioners and the CCB. Significant reform is required, but doing so adequately must take into account a broad discussion among and the views of Canadian stakeholders. Such a discussion – and the eventual reform of the merger notification rules – will produce real benefits for the CCB, for firms attempting to predictably plan the M&A process, and for Canadians.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 Rosner practices competition law at Goodmans LLP in Toronto, Canada. The views expressed in this paper are the author’s alone; this paper does not reflect the views of Goodmans LLP or its clients. The author is grateful to the numerous colleagues who reviewed and provided valuable feedback on drafts of this paper.

2 For example, the European Council’s first merger regulation dates from 1989. The regulation (including its procedural and substantive provisions) was subject to extensive discussion and then replaced with a reformed regulation in 2004. Discussion of the 2004 regulation’s merits and deficiencies has continued. Most recently, the European Commission has studied whether the regulation’s notification obligations should be extended to non-controlling minority investments.

3 See, for example, the recommendations of the International Competition Network – an organization of competition law agencies to which the CCB belongs – which counsels that jurisdictions “should periodically review their merger notification thresholds to determine whether to modify them based on knowledge gained through the application of the thresholds, experiences in other jurisdictions, input from stakeholders, and other pertinent developments.” International Competition Network’s Merger Working Group, Recommended Practices for Merger Notification Procedures (“ICN Recommended Practices”), Section II.B, Comment 4, online: http://www.internationalcompetitionnetwork.org/uploads/library/doc1108.pdf.

4 Such a broad discussion should begin by examining first principles, including basic questions such as (i) whether mandatory merger notification remains advisable in Canada or whether a voluntary merger notification model utilized in jurisdictions like the United Kingdom and Australia is more desirable, and (ii) whether merger notification rules (which are technical and involve different policy objectives) should be severed from other competition laws and included in another Act of Parliament that can be more discretely and technically amended, as advisable.

5 Canada has demonstrated itself capable of such discussions in the past, having engaged in them concerning reform of the notification rules in the Investment Canada Act. That statute formerly provided that pre-closing approval was required for the acquisition of Canadian businesses whose assets exceeded a value threshold. It was reformed, in part, to change the threshold to focus on the enterprise value of the acquired Canadian business.

6 Economic Council of Canada, Interim Report on Competition Policy, 14 Antitrust Bull. 933 1969 (the “1969 Report”) at 935 and 937.

7 The 1969 Report, at 961.

8 Several bills reforming Canadian competition law were introduced in Parliament in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but none were passed into law. Some of these bills contained merger notification rules of different types. See Bill C-256, 3rd Sess., 28th Parl., 1970-71 (first reading June 29, 1971); Bill C-42, 2nd Sess., 30th Parl., 1976-77 (first reading March 16, 1977); Bill C-13, 3rd Sess., 30th Parl., 1977 (first reading November 18, 1977) and Bill C-29, 2nd Sess., 32nd Parl., 1984.

9 See Competition Law Amendments: A Guide, Consumer and Corporate Affairs Canada, Ottawa, 1985 at page 20.

10 See Reform of Competition Policy in Canada: A Consultation Paper, Consumer and Corporate Affairs Canada, Ottawa, 1985, at para. 47. The paper also reiterated the objectives described in the 1969 Report, explaining that “A prior prenotification provision is essential for an effective analysis of the largest, most complex mergers likely to have substantial effects on competition.”

11 The changes to the merger notification rules since their enactment have been minor, and have not modified the rules’ general operation. These changes were to the value of the Size-of-Target threshold, and to introduce two provisions designed to address two types of transactions that were not caught by the rules as originally enacted. In addition, a bill is currently before Canada’s Parliament (Bill C-25, discussed later in this paper) that would address certain other gaps in the rules.

12 See, generally, the ICN Recommended Practices, as well as the merger notification rules in numerous other mature economies that maintain mandatory merger notification rules that pursue these same objectives.

13 For a discussion of the frequency of updating of merger notification rules in other jurisdictions, as well as recommendations for such updating from the ICN, see footnotes 2 and 3, above. One reason the merger notifications rules have not been subject to discussion is that, in 30 years, there has not been a single instance of the “failure to file” provision being enforced (and, as a result, subject to interpretation and comment by a court). For a discussion of the problems of enforceability of the “failure to file” provision, see Section IV, below.

14 In addition, depending upon the transaction structure, there are various non-economic “share” thresholds that must be surpassed in order for a transaction to require a notification. In practice, these thresholds test the degree of control the purchaser is acquiring as a result of the transaction, and exclude non-M&A transactions (such as commercial agreements) from the operation of the merger notification rules. These rules are not discussed further in this paper, and for brevity any “transaction” referenced in this paper is a M&A transaction.

15 Canadians sometimes refer to this threshold as the “size-of-transaction” threshold, even though the threshold measures on the acquired party and not the value paid for the acquired party. This confusing nomenclature is not utilized in this paper.

16 This inconsistency will be resolved if Bill C-25 (discussed below) is passed into law.

17 Other countries with which Canada maintains free trade agreements are Mexico, South Korea, Colombia, Chile, Israel, the four members of the European Free Trade Association and a number of Latin American countries. The jurisdictions with which Canada maintains free trade agreements contain more than 1.2 billion people. For population statistics, see online: http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/population-by-country/.

18 All data indicated is in chained 2007 dollars (i.e., on a constant basis). Import and GDP obtained from Statistics Canada.

19 Statistics Canada altered certain aspects of data collection starting in 1997; to demonstrate changes in different sectors from the present day compared to the past on a like-for-like basis, 1997 (i.e., the earliest available data) was utilized for comparison purposes.

2 For a discussion of the relationship between these new industries and competition policy, see CCB, Big data and Innovation: Implications for competition policy in Canada (draft; published for public consultation), September 18, 2017, online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/04304.html, including the discussion of merger notification rules at page 20.

21 Statistics about the number of notifications received by the CCB from the past ten years are available from a Merger Review Performance Report, April 12, 2012, online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/03452.html, covering the years 2007 – 2012; the CCB’s monthly reports of concluded merger reviews, online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/02435.html; and various quarterly reports issued by the CCB, see online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/h_03803.html.

22 Notably, in 2012 the CCB published for public consultation a draft “interpretation guideline” that took an aggressive view as to whether assets (particularly those that were intangible or movable) were considered to be located in Canada and whether revenues were to be classified as import or domestic when applying the economic thresholds (“IG#15”). If implemented IG#15, would likely have resulted in additional transactions (mainly involving at least one non-Canadian firm) becoming notifiable. However, IG#15 was never formally adopted by the CCB. See CCB, “Pre-Merger Notification Interpretation Guideline Number 15: Assets in Canada and Gross Revenues from Sales in, from or into Canada, April 11, 2012, online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/03153.html.

23 CCB Presentation, “Merger Review Performance Report: Update on Key Performance Statistics”, Annual Roundtable Meeting organized by the Canadian Bar Association, May 26, 2017 (Toronto: Canada), at slide 10.

24 The only action taken by the CCB in either sector known to the author is an investigation almost 15 years ago regarding a potential conspiracy in the real estate industry in Toronto. Given the passage of time, the investigation is believed to have been abandoned. See Cadillac Fairview Corp. v. Canada (Commissioner of Competition), 2003 CanLII 47009 (ON SC), online: https://www.canlii.org/en/on/onsc/doc/2003/2003canlii47009/2003canlii47009.html.

25 See the ICN Recommended Practices, Section II, B, Comment 3 (“… The sales and assets of the selling group or the selling party that are not being transferred to the acquiring party should not be considered in applying the merger notification thresholds”).

26 Including the affiliates of the purchaser and subsidiaries of the target.

27 See the ICN Recommended Practices, Section II, C. Comment 2 explains that, “Many jurisdictions require significant local activities by each of at least two parties to the transaction as a prerequisite for mandatory merger notification. This approach represents an appropriate material nexus screen since the likelihood of adverse effects from transactions in which only one party has a significant local presence is sufficiently remote that the burdens associated with notification are normally not warranted.” Comment 4 warns that, “jurisdictions with notification thresholds based solely on the activities of the acquired business should set their thresholds at a substantially higher level to ensure that the transaction has a material nexus to the reviewing jurisdiction.”

28 For example, Corporation 1 generates revenues from sales in and from Canada of $201 million, and Corporation 2 generates revenues from sales into Canada (i.e., import sales) of $200 million. Corporation 1 agrees to acquire Corporation 2. The proposed transaction is not notifiable because while Corporation 1 and 2 on a combined basis satisfy the Size-of-Parties threshold, Corporation 2 does not satisfy the Size-of-Target threshold (all of its Canadian sales are import sales). However, if Corporation 2 buys Corporation 1, a notification is required because Corporation 1 and 2 on a combined basis satisfy the Size-of-Parties threshold and Corporation 1 satisfies the Size-of-Target threshold (all of its sales are domestic and export).

29 More generally, the CCB agrees with the contention that activity that affects competition in Canada, even if it originates outside of Canada, should be subject to the Act. See, for example, the CCB’s pleadings in Commissioner v. HarperCollins Publishers L.L.C. and HarperCollins Canada Limited, CT-2017-002, and in particular the CCB’s Memorandum of Fact and Law of the re: Motion to Strike / Dismiss the Application filed April 4, 2017, starting at para. 25, online: http://www.ct-tc.gc.ca/CMFiles/CT-2017-002_xxx_54_66_4-7-2017_2038.pdf.

30 See, for example, Items 2, 5 and 6 of the U.S. Hart-Scott-Rodino Act notification and report form, and Sections 3 and 4 of the European Commission’s Form CO. It is also notable that information of a similar type is collected under the Investment Canada Act.

31 See Affidavit of Nicholas Janota, affirmed July 21, 2016, at para. 10, filed in Commissioner of Competition v. Dow Agrosciences Canada Inc. and Dow Chemical Canada ULC, Court File No. T-1221-16.

32 See CCB press release, “Competition and innovation are preserved following major agricultural merger”, June 27, 2017, online: https://www.canada.ca/en/competition-bureau/news/2017/06/competition_and_innovationarepreservedfollowingmajoragricultural.html?wbdisable=true.

33 The anti-avoidance provision in the United States is found in U.S. Regulation 16 CFR §801.90, which provides that, “Any transaction(s) or other device(s) entered into or employed for the purpose of avoiding the obligation to comply with the requirements of the act shall be disregarded, and the obligation to comply shall be determined by applying the act and these rules to the substance of the transaction”; see online: https://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?SID=0985c3db2db851a507d4d3c484fa7019&mc=true&node=pt16.1.801&rgn=div5. By further example, see Article 5.2, paragraph 2 of the European Commission’s Merger Regulation, which provides that “two or more transactions within the meaning of the first subparagraph which take place within a two-year period between the same persons or undertakings shall be treated as one and the same concentration arising on the date of the last transaction”; see online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/ALL/?uri=CELEX:320040139. The European Commission’s Consolidated Jurisdictional Notice explains at para. 49 that Article 5.2, paragraph 2 is to ensure that “the same persons do not break a transaction down into series of sales of assets over a period of time, with the aim of avoiding the competence of conferred on the Commission by the Merger Regulation”; see online: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:C:2008:095:0001:0048:EN:PDF.

34 See, for example, section 245 of Canada’s Income Tax Act, which provides “Where a transaction is an avoidance transaction, the tax consequences to a person shall be determined as is reasonable in the circumstances in order to deny a tax benefit that, but for this section, would result, directly or indirectly, from that transaction or from a series of transactions that includes that transaction.”

35 The Act recognizes that transactions among affiliates should not be subject to notification, and includes an express exemption for such purposes; see s. 113(a) of the Act. However, problems with the Act’s affiliation rules mean that some transactions among entities that are affiliates as a matter of fact do not benefit from the exemption.

36 This assumes Corporation 3 is not controlled by a vendor with revenues in, from or into Canada greater than $300 million. This example also assumes that the asset thresholds are not exceeded.

37 See Bill C-25, An Act to amend the Canadian Business Corporations Act, the Canada Cooperatives Act, the Canada Not-for-profit Corporations Act, and the Competition Act, 1st reading September 28, 2016, 42nd Parliament, 1st Session, at sections 109 and 110, online: http://www.parl.ca/LegisInfo/BillDetails.aspx?Language=E&billId=8433563.

38 See, for example, CCB, Statement regarding the three-part inter-conditional transaction between GlaxoSmithKline plc and Novartis AG involving their consumer healthcare, vaccines and oncology businesses, February 23, 2015, online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/03874.html (referencing the fact that only one of three transactions between the parties was subject to notification).

39 See U.S. Regulation 16 CFR §801.13 to §801.15 for the U.S. transaction aggregation rules and footnote 33, above, for the European transaction aggregation rules.

40 The obligation to aggregate would spring upon the occurrence of a second transaction (and any subsequent transaction), such that the subsequent transaction would have to be aggregated with all previous transactions between the same parties within the defined time period.

41 See CCB, Pre-Merger Notification Interpretation Guideline Number 4: Exemption for Combinations that are Joint Ventures, June 20, 2011, online http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/03361.html.

42 The limited policy purpose of the exemption is set out in section 95(1)(a) of the Act.

43 In the only case the CCB is publicly known to have taken action in respect of a failure to file, the CCB took the view that rather than proceed with a criminal charge it was appropriate for the company in question to “adopt a compliance program to ensure it complies with the Act in the future.” See CCB, Competition Bureau takes steps to ensure Parrish and Heimbecker complies with pre-merger notification obligations, May 29, 2015, online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/03948.html. This is to be contrasted with the significant actions that can be taken or pursued by competition law agencies in other jurisdictions in response to a failure to file.

44 See CCB, Competition Bureau’s proposal to increase the filing fee for merger reviews, October 20, 2017, online: http://www.competitionbureau.gc.ca/eic/site/cb-bc.nsf/eng/04311.html

Featured News

T-Mobile’s Acquisition of Ka’ena Corporation Receives FCC Approval

Apr 26, 2024 by

CPI

UK Regulator Announces Two New Senior Executive Appointments

Apr 26, 2024 by

CPI

Paramount Global and Skydance Media Near Merger Deal, Eyeing CEO Change

Apr 26, 2024 by

CPI

BHP Unveils £31bn Mining Megamerger Proposal with Anglo American

Apr 25, 2024 by

nhoch@pymnts.com

ByteDance Prefers Shutdown Over Sale of TikTok Amid US Ban Threats

Apr 25, 2024 by

CPI

Antitrust Mix by CPI

Antitrust Chronicle® – Economics of Criminal Antitrust

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

Navigating Economic Expert Work in Criminal Antitrust Litigation

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

The Increased Importance of Economics in Cartel Cases

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

A Law and Economics Analysis of the Antitrust Treatment of Physician Collective Price Agreements

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

Information Exchange In Criminal Antitrust Cases: How Economic Testimony Can Tip The Scales

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI