By Matthew Spitzer (Northwestern University)1

The

District Court’s opinion finding Qualcomm guilty of antitrust violations in a

case brought by the Federal Trade Commission2 is

on appeal to the Ninth Circuit. This post will show that the circumstances

under which the FTC chose to bring this case should lead everyone, including

the Court of Appeals, to view this case with skepticism.

The

Federal Trade Commission’s case against Qualcomm for allegedly violating

Section 2 of the Sherman Act (monopolization) was initiated in a most unusual

and troubling fashion.

- The FTC is supposed to have five members. However, at the time the FTC voted to bring the case, there were only three sitting members. Gridlock between the President and the Senate had prevented filling the vacancies.

- The vote to bring the case was 2 to 1, along party lines.3

- There was a written dissent by Commissioner Maureen Ohlhausen from the decision to bring the case.

- One of the two Commissioners who voted to bring the case (Chairperson Edith Ramirez) announced her resignation on January 13, four days before the vote to bring the case.4

- The vote was taken on January 17, 2017, three days before the inauguration of a new President, during the “lame duck” period. The new President represented a change of the party in power.

How

disquietingly unusual was this procedural setting? Very unusual and very

disquieting, as it turns out.

To

examine this question, I5

scraped the FTC’s website to gather all of the votes on bringing, settling, or

taking court action in antitrust monopolization actions (excluding Hart-Scott-Rodino

filings) since 1994.6

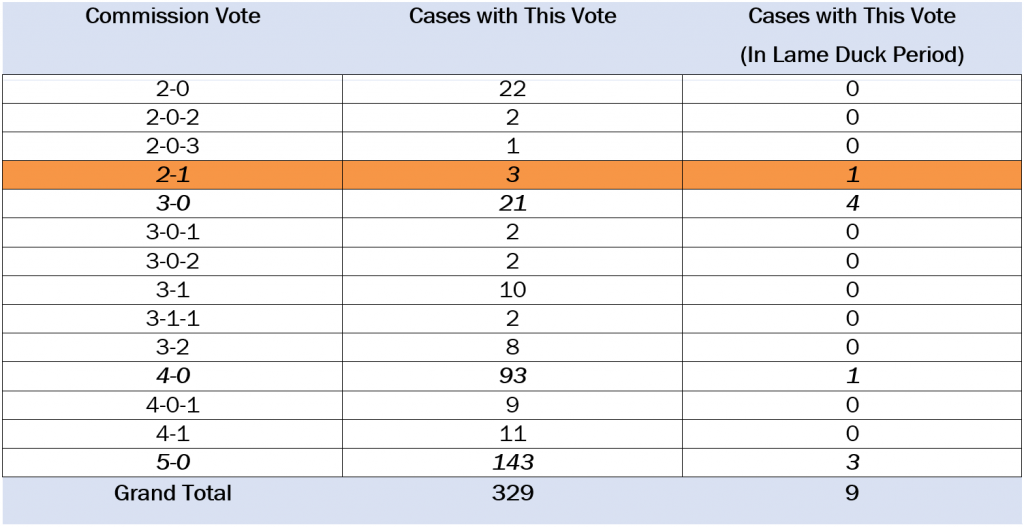

There have been 329 such actions, and the votes are summarized in the table

below. The numbers in the first row indicate votes for, votes against, and

recusals. Thus, 4-0 indicates four votes for, zero against, and no recusals.

And 4-0-1 indicates four votes for, zero against, and one recusal. Thus, the

4-0 vote also indicates that the FTC had only four members, while the 4-0-1

vote shows that the FTC was at full strength. Any row with a “lame duck” period

vote is shown in bold and italics. The category into which the FTC’s decision

to bring an action against Qualcomm falls (2-1) is highlighted.

The

columns may need a bit of explanation. The first column shows the outcome of

the vote in all the cases since 1994 detailed in that row. The second column

shows the total number of cases since 1994 that had that vote. And the third

column shows the total number of cases since 1994 that had that vote and

that were brought in the lame duck period. Thus, the entries in the third

column are also represented in the second column.

The

first thing to note is that only 3 of the 329 cases were brought by a 2-1 vote.

That is less than 1%. And the only one of those to be brought during the lame

duck period was FTC v. Qualcomm.

Second, if we add in the 3-2 votes, the only others where there is a one-vote

margin, we get 11, or about 3%. Why focus on these? They are the cases where

the wisdom of bringing the case is most suspect. A multimember expert body,

such as the FTC, is supposed to apply its wisdom to the decision to bring a

case. Where the decision is brought on a razor thin vote, the wisdom is also

razor thin. Not surprisingly, only 3% of the cases brought are in this

category.

To

turn this around, the typical way to bring a case is by unanimous vote. This is, by definition, where all Commissioners

agree. If we sum the 5-0, 4-0, and 4-0-1, 3-0, 3-0-1, and 3-0-2 (all of the

unanimous votes with at least 3 votes in favor) we get 270 of the 329 cases, or

82%. If we throw in the 27 cases with 2-0, 2-0-2, and 2-0-3, we have 297 of the

329 cases, or 90%. Thus, 90% of the cases are unanimous. These are the cases

where our belief is that the case is strongest. And the 4-1 and 3-1 cases lie

in between the unanimous cases and the “razor thin margin” cases in terms of

likely strength of case.

What about cases brought in the “lame duck” period – between the date of the election of a new President from a different party and the inauguration?7 These are cases where we should be most suspicious that the case is politically motivated. After all, if there were no political motivation for the case, the Commissioners would just put the case on the back burner for a few weeks and allow the new President’s appointees to make the decision about whether to bring the case. There are only nine votes in the lame duck period in the data set, and only one of these had a dissenting vote – FTC v Qualcomm.

Thus,

the vote to bring FTC v Qualcomm

provides the least wisdom and confidence of any vote to bring any FTC antitrust

case since 1994. The vote, 2-1, was the least likely to signal a meritorious

case in the data set, while bringing it in the lame duck period suggests

political considerations produced it.

So,

what are the implications of all of this? Everyone – courts, journalists, law

professors, techies, and the general public – should view this case with a

great deal of skepticism. Or, to put the same point differently, there should

be a very high burden of proof on the FTC.

What happened after the vote to bring the case? On November 6, 2018, Judge Koh handed down an opinion8 finding that Qualcomm violated Section 2 of the Sherman Act and ordered far-reaching remedies. These remedies are so broad that they threaten to disrupt the worldwide modem chip business. The remedies have now been stayed by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.9 While staying the remedies the court stated that “Qualcomm has shown, at minimum, the presence of serious questions on the merits.”10 The case is now before the Ninth Circuit. I am not surprised that there are serious questions on the merits. The circumstances of bringing this case in the first place virtually guaranteed that there would be questions. One can only hope that the Ninth Circuit will take a very close look at this case, and that the FTC will refrain from bringing any more cases under similar circumstances.

Click here for a PDF version of the article

1 I am Director of the Northwestern University Center on Law, Business, and Economics. Before that I was the Director of Northwestern’s Searle Center on Law, Regulation, and Economic Growth. The Searle Center received its largest gift (by far) from the late Dan Searle. It also received very major funding from Qualcomm, and smaller (but still very significant) funding from Microsoft, Google, the USPTO, Intellectual Ventures, and many others. For a full list, please visit http://www.law.northwestern.edu/research-faculty/clbe/documents/searle_center_support.pdf.

2 Federal Trade

Commission v. Qualcomm Inc., 2018 WL 5848999, Nov. 6, 2018, N.D. Cal.

3 The FTC, after getting a full contingent of

Commissioners, reconsidered the wisdom of bringing the case. The FTC split 2 to

2, with the Chairperson recusing himself because Chair’s former law firm had

represented Qualcomm.

4 How often is the deciding vote in favor of bringing

the case cast by a Commissioner who had already announced her resignation? That

turned out to be more difficult to chase down than the other aspects of this. I

am still working on it.

5 To be more accurate, my research assistant, Adam

Gilmore, did the scraping.

6 A more complete description can be found at http://bit.ly/ftc_search_description.

7 In our data set those would be Bill Clinton to George

W. Bush; Bush to Obama; and Obama to Trump.

8 Federal Trade

Commission v. Qualcomm Inc., 2018 WL 5848999, Nov. 6, 2018, N.D. Cal.

9 FTC v. Qualcomm

Inc, 935 F.3d 752, Aug 23, 2019 (9th Cir.)

10 Id. at 756.

Featured News

T-Mobile’s Acquisition of Ka’ena Corporation Receives FCC Approval

Apr 26, 2024 by

CPI

UK Regulator Announces Two New Senior Executive Appointments

Apr 26, 2024 by

CPI

Paramount Global and Skydance Media Near Merger Deal, Eyeing CEO Change

Apr 26, 2024 by

CPI

BHP Unveils £31bn Mining Megamerger Proposal with Anglo American

Apr 25, 2024 by

nhoch@pymnts.com

ByteDance Prefers Shutdown Over Sale of TikTok Amid US Ban Threats

Apr 25, 2024 by

CPI

Antitrust Mix by CPI

Antitrust Chronicle® – Economics of Criminal Antitrust

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

Navigating Economic Expert Work in Criminal Antitrust Litigation

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

The Increased Importance of Economics in Cartel Cases

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

A Law and Economics Analysis of the Antitrust Treatment of Physician Collective Price Agreements

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI

Information Exchange In Criminal Antitrust Cases: How Economic Testimony Can Tip The Scales

Apr 19, 2024 by

CPI